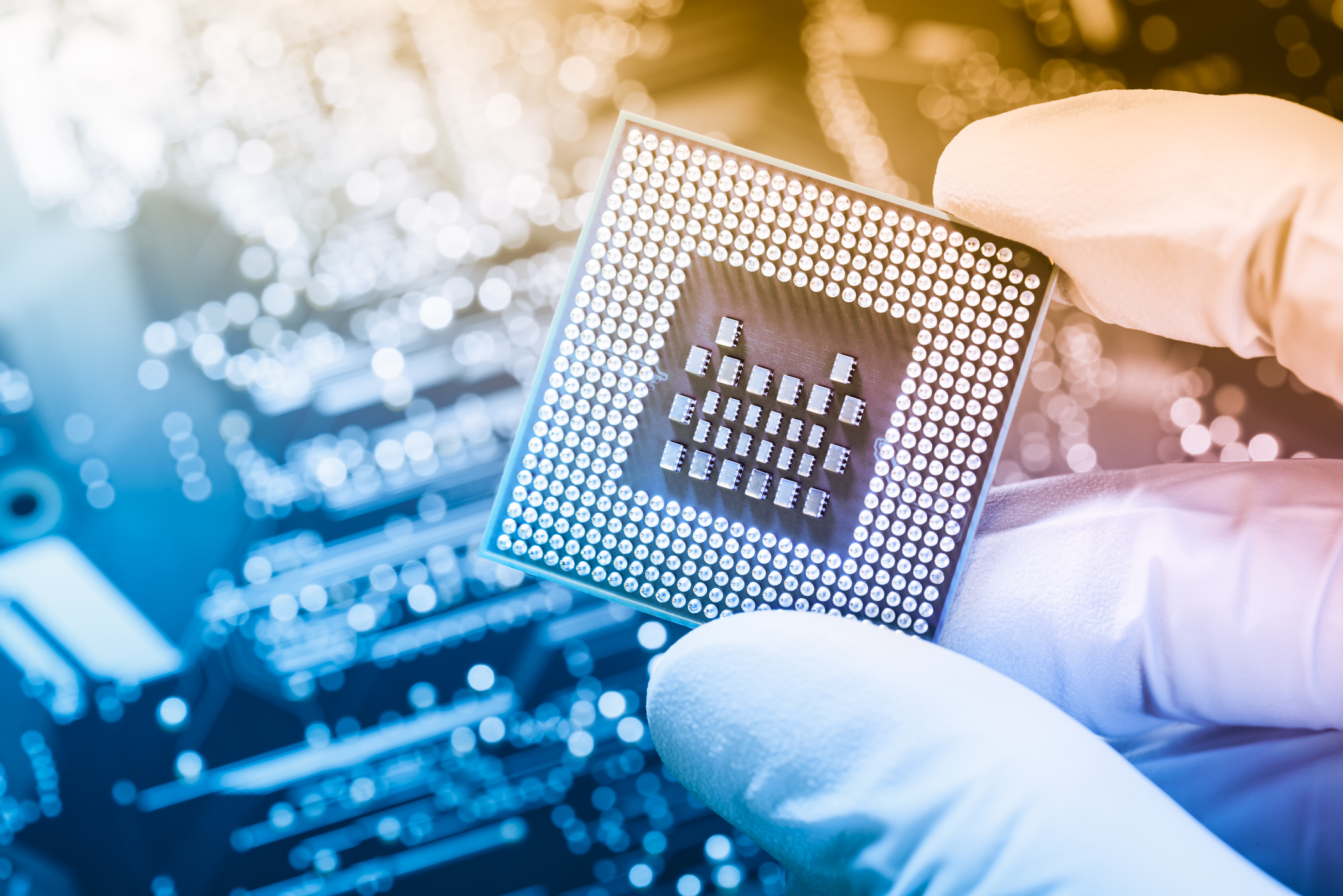

SUPPLY CHAIN ISSUES for computer chips became mainstream news this year, as car lots emptied and electronics store shelves stayed bare. The logjam is unwinding, but playing catch-up will continue for most or all of 2022, delaying some new products.

“I hate when people say it’s a fab [fabrication foundry] issue when it’s the substrate, the fab, the back-end assembly, test capabilities, and other issues,” says Jim McGregor, principal analyst at TIRIAS Research. “COVID created a couple of years of Christmas in a two-month period, as work from home and all sorts of other demand skewed toward tech.” Even worse, chips for the industrial and automotive markets are three to five generations old and will have to move to newer fabs with 300 nm wafers to get volume again, adds McGregor.

Companies with their own fabrication foundries are in a better situation, says McGregor. “There are the haves and have-nots. Foundries told vendors to put money in for future fab growth or go to the back of the line for product.”

Vendors like Intel, with their own plants, or NVIDIA, with the money to help partner Samsung build new manufacturing lines, will recover first. Smaller vendors with no foundries or close partnerships will remain behind. “2022 may still have limited fab capacity,” adds McGregor, “so relief will be delayed until late 2023 or even 2024.”

This can leave system builders in a bind, says Jon Peddie, president of Jon Peddie Research. “Be very nice to your customers,” he advises. “Integrators, VARs, and OEMs are going to have to raise prices.” That, of course, could end up reducing sales.

McGregor suggests multisourcing. “Intel may not have the best products in some chip lines, but they have availability. Get products where you can and consider moving from an Intel-only model to maybe offer systems with AMD chips.” In addition, he suggests you allocate capacity to the most critical products and do long-term forecasting to get more purchasing power from suppliers.

Looking to what’s ahead for the year, McGregor says chipmaker roadmaps “aren’t changing that much.”

Chip announcements from Intel include the 12th Gen Alder Lake chip family, which like other forthcoming products the company now calls “Intel 7” processors rather than 10 nm, says Peddie. “This is while AMD uses 7 nm and Apple’s M1 is built on a 5 nm node.” Alder Lake chips finally appeared in late 2021, and the Sapphire Rapids chips for data centers should appear in 2022. Intel’s 13th Gen Raptor Lake chips for the desktop should also appear later in 2022.

Qualcomm’s Snapdragon 8 Gen 1 flagship for its mobile system on a chip (SoC) uses a 4 nm process and will take the lead from the Snapdragon 888.

On the graphics side, Intel’s new Arc Alchemist GPUs, using its Xe Super Sampling Tech (XeSS), should arrive in the second quarter to compete against NVIDIA and AMD. NVIDIA’s new intro GPU, the RTX 3050, should cost less than $300, and the rumored RTX 3090 Ti may finally appear, bringing 40 teraflops of GPU horsepower.

These rollouts are more evolution than revolution, according to McGregor. “Vendors with a broad array of chips, like Intel, will focus on the models with plenty of supply, giving up market share in desktops, perhaps, to focus on servers and mobile.” More stock and more profit mean a win for chip makers.

Until new fabrication facilities can come online, demand will continue to squeeze supply, says McGregor. “Esports are bigger than every other sport in the world, boosting companies like Qualcomm for handheld consoles.” There’s also huge demand for traditional consoles, which may continue for the rest of the decade in some areas.

Going forward, Peddie says Moore’s Law remains alive and well, so expect more of everything, including cores, memory capacity, and speed. “And,” he adds, “they’ll be more expensive.”

Image: iStock